What Watching My Kids Argue Taught Me About Power, Not Behavior

For years, I thought sibling arguments were primarily about behavior. Who took what.Who started it.Who crossed the line first. I listened for tone, counted rule violations, and stepped in when things escalated past what I considered acceptable. Like many parents, I believed my role was to correct the behavior quickly so the situation didn’t spiral…

For years, I thought sibling arguments were primarily about behavior.

Who took what.

Who started it.

Who crossed the line first.

I listened for tone, counted rule violations, and stepped in when things escalated past what I considered acceptable. Like many parents, I believed my role was to correct the behavior quickly so the situation didn’t spiral into something bigger.

What I didn’t realize was that I was focusing on the least important part of what was actually happening.

It wasn’t until I stopped trying to fix the argument and started watching it that I understood what my kids were really negotiating.

They weren’t arguing about toys, space, or fairness.

They were arguing about power.

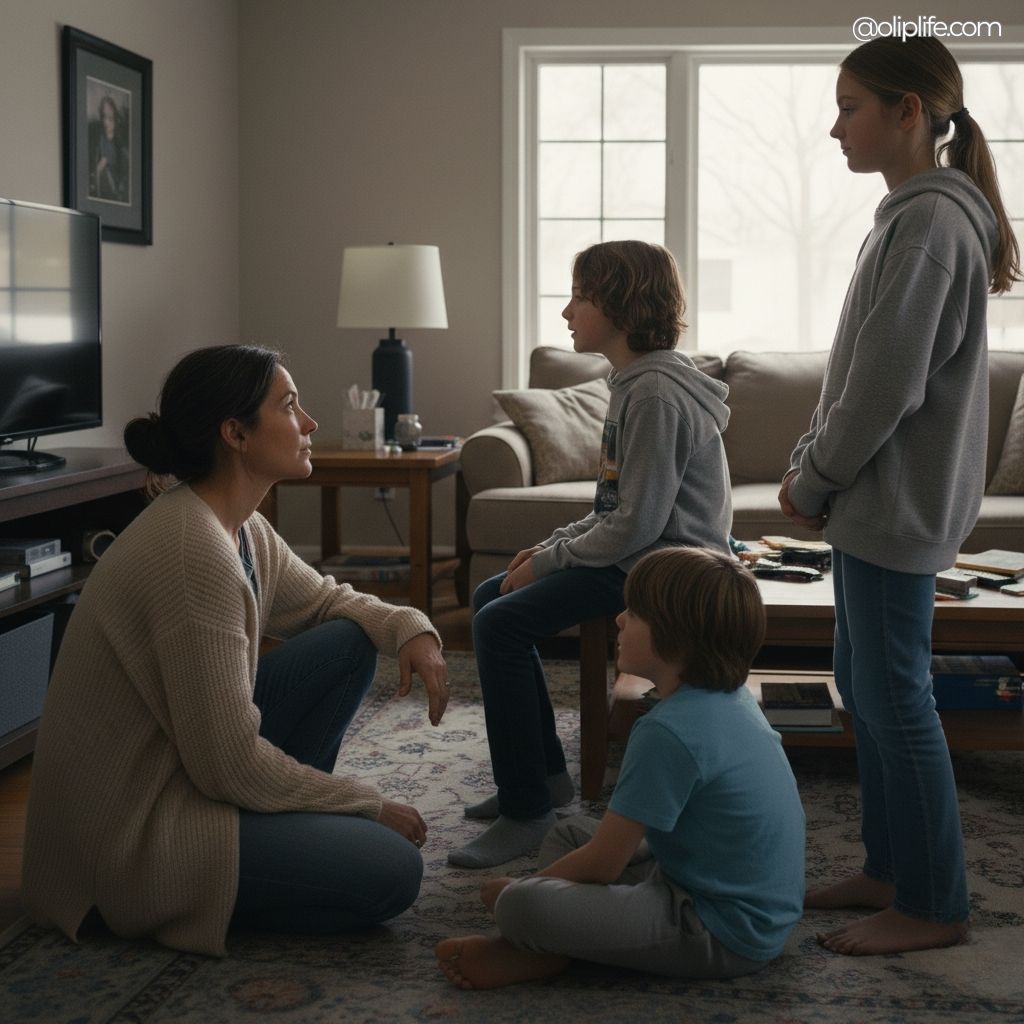

The Argument That Looked Like Chaos

The argument that finally shifted my perspective wasn’t louder or more dramatic than the others. It was familiar enough that I almost intervened on autopilot.

Ben wanted something Owen had. Owen wanted control over how it was used. Lucy was involved tangentially, not because she cared about the object, but because she cared about how the situation was unfolding.

Voices rose. Bodies angled toward each other. Each child tried, in their own way, to gain leverage.

My instinct was to step in and separate them, assign responsibility, and restore order. That had always been my approach.

This time, I waited.

Not long enough for things to get unsafe, but long enough to notice something I had been missing for years.

Each child was using the tools available to them.

How Each Child Tried to Gain Control

Ben used words.

He argued his case relentlessly, stacking logic on top of logic, insisting on fairness, precedent, and consistency. He wasn’t just asking for the object. He was asking to be taken seriously. He wanted his reasoning to carry weight.

Owen used volume and physical presence.

His frustration showed up in his body before it reached his language. He moved closer, raised his voice, asserted himself through proximity and intensity. He wasn’t trying to be aggressive. He was trying to avoid being overpowered.

Lucy withdrew strategically.

She stepped back, observing, waiting to see which way the balance would tip. She didn’t need the object or the outcome as much as she needed the emotional temperature to lower. Her power move was disengagement.

Three children. One argument.

Three different approaches to the same underlying question.

Who has influence here?

Why Behavior Was the Wrong Lens

When I viewed the argument through the lens of behavior, I saw problems to fix.

Ben was being argumentative.

Owen was being reactive.

Lucy was being avoidant.

Each label came with a corresponding correction.

Stop arguing.

Lower your voice.

Don’t walk away.

But none of those corrections addressed what the kids were actually trying to solve.

They weren’t struggling with behavior.

They were struggling with hierarchy, autonomy, and agency.

Sibling arguments are rarely about the surface issue. They are negotiations about who gets to decide, who gets to resist, and who has to adapt.

Once I saw that, everything changed.

Power Isn’t a Bad Word in Families

For a long time, I avoided thinking about power in our home because it felt uncomfortable.

Power sounded harsh. Authoritarian. Something parents wielded, not something children negotiated among themselves. But power exists in every relationship, whether we name it or not.

Between siblings, power shows up constantly.

Who is older.

Who is stronger.

Who speaks better.

Who adapts faster.

Children learn quickly where they have leverage and where they don’t. Arguments are often the testing ground for that knowledge.

When I treated those arguments as misbehavior, I missed the opportunity to help them understand and navigate power more responsibly.

What Happened When I Changed My Response

Instead of stepping in to stop the argument, I began stepping in to slow it down.

I stopped asking, “Who started it?” and started asking, “What are you trying to make happen right now?”

The answers were revealing.

“I want him to stop deciding everything.”

“I want her to listen to me.”

“I don’t want to lose.”

Those weren’t bad intentions.

They were honest ones.

Once the kids felt seen in that deeper layer, the argument shifted. Not instantly, and not every time, but often enough to matter.

How Each Child’s Strategy Made Sense

When I stopped correcting behavior and started naming power dynamics, I could see how logical each child’s approach actually was.

Ben argued because words were his strongest tool. He had learned that adults respond to explanation and justification, so he applied that strategy with siblings as well.

Owen escalated physically because his body responded faster than his language, and because intensity often forced others to notice him.

Lucy disengaged because she valued emotional safety over control, and stepping back was the quickest way to restore balance.

None of these strategies were wrong.

They were adaptive.

The problem wasn’t the strategy. It was the lack of awareness around it.

Teaching Power Without Shaming

Once I understood what was happening, my role shifted.

I wasn’t there to eliminate power struggles. I was there to make them visible and safer.

Instead of saying, “Stop yelling,” I began saying, “It sounds like you’re trying to get control back.”

Instead of saying, “You’re being unfair,” I said, “You’re worried you don’t have a say.”

Those shifts didn’t excuse harmful behavior, but they reframed it.

The kids began to recognize their own patterns.

Ben noticed when he was arguing to dominate rather than to understand.

Owen began identifying the moment his body took over.

Lucy started naming when stepping back felt like self-protection rather than choice.

That awareness was more effective than any consequence I had tried before.

What Power Awareness Gave Them

As the kids became more aware of power dynamics, their arguments changed.

Not because conflict disappeared, but because it evolved.

They started negotiating rather than overpowering.

They experimented with compromise instead of escalation.

They recognized when someone else was being sidelined.

Most importantly, they learned that power didn’t have to be taken.

It could be shared.

The Role I Had Been Playing Without Realizing It

Watching my kids argue also forced me to examine my own role in these dynamics.

I realized how often I reinforced certain power structures without intending to.

I sided with the child who communicated most like an adult.

I intervened faster with the child whose reactions made me uncomfortable.

I praised calmness without acknowledging how hard it was to maintain.

Those patterns shaped how the kids argued with each other.

Once I became aware of that, I adjusted.

I listened more evenly.

I validated differently.

I slowed down before stepping in.

The shift wasn’t dramatic, but it was consistent.

Why This Matters Beyond Childhood

Sibling arguments are some of the earliest arenas where children learn about power.

They learn how to assert themselves.

They learn how to resist.

They learn when to comply and when to push back.

If parents treat those moments purely as behavioral problems, children miss the chance to develop healthy power literacy.

They grow up either overpowering others or avoiding conflict altogether.

Neither outcome serves them well.

What I Know Now

Watching my kids argue taught me that behavior is often just the language power uses when it hasn’t been translated yet.

Once children have the language for what they’re really negotiating, arguments lose some of their intensity.

They don’t disappear.

They become more honest.

Final Thoughts

Sibling conflict isn’t a sign that something is going wrong.

It’s evidence that children are learning how to exist alongside others with competing needs and limited control. That learning is messy, loud, and uncomfortable at times.

When parents stop focusing solely on behavior and start paying attention to power, they gain a deeper understanding of what their children are actually working through.

That understanding allows us to guide rather than control, to teach rather than suppress, and to raise children who don’t just behave well, but who understand how to navigate influence, boundaries, and agency with awareness and respect.

And that lesson, learned early and reinforced often, stays with them far longer than any rule we enforce in the heat of the moment.